Gongabu: two streets with children working in small-scale businesses associated with the Adult Entertainment Sector

Gongabu is a large area in the north of Kathmandu that is home to the capital’s largest bus park. The bus park is situated on the south side of the Ring Road – the capital’s highway that circles the city and runs through the centre of Gongabu. As well as serving as a local bus terminus, the bus park connects the capital to the regions of Nepal. The area is a major transition point; a gateway for individuals traveling from the districts of Nepal to migrate overseas or to visit Kathmandu, as well as a transport hub for those living in the city. It is situated close to the Ring Road – the capital’s highway that circles the city and runs through the centre of Gongabu.

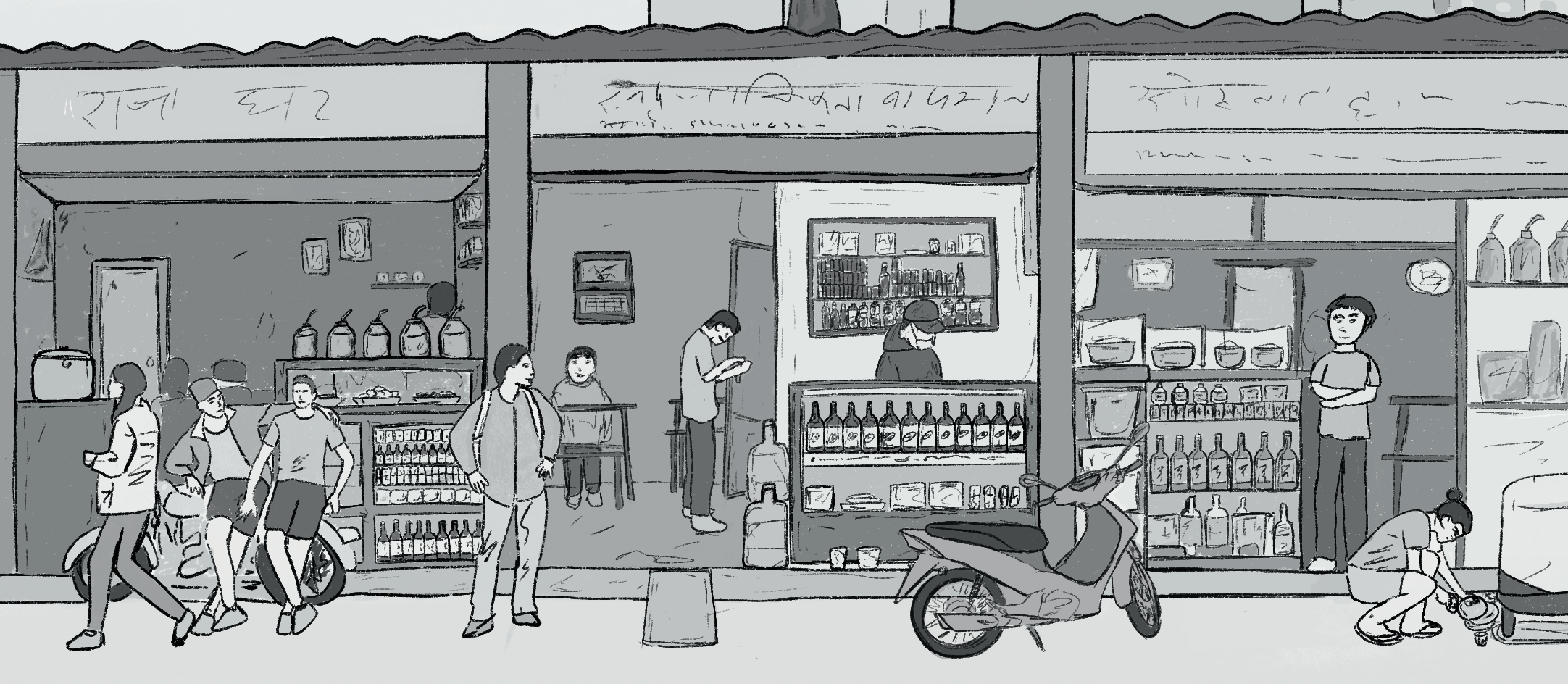

One of the streets mapped by CLARISSA is in Gongabu, close to Kathmandu’s main bus park. The street serves both domestic travellers passing through Kathmandu and local residents. Night entertainment venues and party palaces exist alongside small-scale businesses such as khaja ghars (snack shops), tailors and barber shops.

Leading off from both sides of the Ring Road, multiple streets cater to the needs of those passing through, whether for a few hours, days or for a longer stay. While the larger streets run from north to south from the ring road, and contain a mixture of businesses – from small-scale restaurants, pharmacies and sweet shops to larger guest houses and entertainment venues – a multitude of narrow thoroughfares run between them, each lined with khaja ghars (small-scale snack shops), small guest houses and other informal businesses.

The area is crowded, and noisy and polluted due to the heavy traffic on the Ring Road. As well as the vehicle pollution, the surrounding streets feel dusty and smoky due to the open fires used to prepare a range of snacks, including sweetcorn and sekuwa (barbequed meat). While Kathmandu is generally a city with high levels of air pollution, Gongabu feels particularly polluted with dust particles and smoke clearly visible in the air.

In 2023, over the course of two days, a team of CLARISSA researchers, including child researchers, spent two days mapping this street in Gongabu and observing children that they saw working on the street. They recorded the children’s age, the type of work they were undertaking and the risks they were exposed to.

Gongabu is an area of haphazard development, where businesses have been rapidly set up in response to the establishment of the bus park as the capital’s main road transport hub over the last 10 to 15 years. A feature of the Gongabu area is the high number of small-scale and highly informal businesses that co-exist with larger-scale businesses. In addition to the commercial street in the area containing a high number of night entertainment venues, two streets with a high proportion of small-scale businesses were chosen by CLARISSA for participatory neighbourhood mapping. On one section of the street there is a dohori, a dance bar, a party palace, guest houses as well as many small businesses such as barbers, grocery shops, tailors and khaja ghars (snack shops); this leads into a narrower street lane which is lined on both sides by small-scale khaja ghars. The street is representative of many similar streets that surrounds it which also contain multiple khaja ghars and guest houses. The businesses serve both passing trade and local residents and have a more residential feel than the commercial street described here.

Khaja ghars are small-scale businesses that serve snacks and alcohol. They are often run by women. Khaja ghars line both sides of the narrow street selected for CLARISSA neighbourhood mapping. The street is representative of many other similar streets in the neighbourhood which compete for business from local residents and domestic travellers entering or exiting Kathmandu by bus.

Many businesses on the street are small enterprises with only one or two people working in them. Although visible from street-level, the research team found it difficult to observe the activities taking place inside without being noticed by the proprietors. The research team visited several khaja ghars for refreshments in smaller groups which provided opportunities to talk with the owners and employees and observe what was taking place within the businesses.

The map developed by the research team shows that in the selected 180-meter section of the two streets there are approximately 100 businesses. This includes more than 30 khaja ghars, one dance bar, and a dohori restaurant.

The map shows where the research team saw children working. More than 20 children were seen working in around 15 businesses or on the street.

Map key

-

Girl

-

Boy

-

Girl

-

Boy

-

Street food vendor

-

Alcohol vendor

-

Goods delivery rickshaw

-

Vegetable vendor

-

Barbecued sweetcorn vendor

-

Samosa vendor

-

Shoe repair/ cobbler

-

Taxi

-

Rickshaw taxi

-

Motorbike taxi

-

Guest house/Hotel

-

Restaurant (incl. coffee shop, fast food)

-

Khaja Ghar (snack shop)

-

Dohori (folk dance bar)

-

Massage parlour

-

Dance bar

-

Pool house

-

Travel agent

-

Bus ticket agent

-

Currency exchange

-

Trekking agent

-

Convenience store

-

Clothing shop

-

Bakery

-

Butcher

-

Sweet shop

-

Pharmacy

-

Fancy goods shop

-

Toy shop

-

Liquor shop

-

Fruit shop

-

Mechanic

-

Photo shop/studio

-

Bank

-

Phone repair shop

-

Hairdresser

-

Spiritual services

A digitalised version of a map created by children and business owners comprising a CLARISSA research team – they mapped the street in detail and observed where children were working

The street

A CLARISSA research team observed the in two shifts between 7am and 8pm on a Friday and Saturday in May 2023. The street was busy in the morning and in the evening, with a quiet period during the day.

The research team observed that khaja ghars are a key feature of the street; they often bore the names of the districts from which their proprietors came from, showing the importance of identity and heritage to those migrating to Kathmandu:

I realised that people like to connect with their identities and where they came from. The names of the khaja ghars were based on the district they came from.

Female, Age 18, Research team

However, some of the khaja ghars had no names and it is likely that some are not registered with the relevant government authorities. Many khaja ghars in the area are started up with very low levels of investment (often by women with few other options to earn a living) and may be set up, shut down or shifted to other premises within short spaces of time because they are not operating in accordance with government regulations and need to avoid scrutiny.

Sounds of the street

More sounds of the street

Khaja ghars normally open at around 6am to serve tea and breakfast to domestic travellers transiting through Kathmandu who stay in nearby guest houses, as well as to local residents:

I believe some customers were travellers staying in guesthouses, and some were people who looked like they were on their way work and wearing good clothes, so might be local but live somewhere where they cannot cook, so they come here to eat in the mornings.

Male, age 16, research team

The research team noted the generally unhygienic conditions in these eateries including uncovered food, and kitchens which looked oily and dirty. Customers were smoking in many of the khaja ghars, and the sale of alcohol (including illegally sold home-made alcohol) is common. Child members of the CLARISSA research team raised concerns about the potential risks for children working in this environment:

We could smell the cigarette in many of the khaja ghars. There were no signs saying people couldn’t smoke. And I could also see almost in every grocery shop there was a sign for Mavic cigarettes as an advertisement. I could see people smoking cigarettes in most of the shops and I believe it is not a good practice as the children walking on the road, or children working or remaining in khaja ghars could learn to smoke. The case with alcohol is the same; almost all of the khaja ghars sell alcohol.

Male, age 16, research team

The research team observed three young boys in the street, one as young as 12, who were chain smoking.

As morning turned to afternoon groups of teens, both boys and girls, gathered in several khaja ghars, to eat and drink and chat.

Throughout the day, an array of street-vendors were observed on the street, selling ice cream, vegetables, and fruit.

The street was busy with a range of people coming and going. This included mainly male travellers, many of whom were looking for guesthouses or taxis, groups of adolescents (boys and girls) hanging around, and men who seemed to live or work in the area.

I saw a few customers might have come from the bus park as they had luggage and they looked tired. Labourers were also eating in the khaja ghars. There were a lot of people who smoked, they were young guys around the age of 18 to 20.

Female, age 18, research team

Male travellers heading to work overseas seemed prevalent. The research team observed negotiations taking place on the street between overseas migration agency staff and young men who were seeking opportunities to work overseas.

A group of younger guys were talking with a person I believe was an agent to send guys abroad. They were in front of a khaja ghar. The agent was trying to convince the young guys to go abroad, talking about different opportunities and salaries; he was especially focusing on Europe and countries like Malta, Romania, and such.

Female, age 18, research team

The general street environment is representative of the area – a lack of footpaths and unmanaged parking makes the road difficult to navigate, and the infrastructure is of poor quality:

There was no footpath for people to walk and the khaja ghar street was congested. The parking isn’t managed, and the roads have lots of ditches and small puddles of water as well as mud.

Male, Age 16, Research team

Local residents were also observed in the street. For example, some children were seen playing in the street and returning from school.

A dohori sits atop a small restaurant on a street that houses a range of businesses and caters to the needs of residents and travellers.

Running a khaja ghar business in the street

Members of the CLARISSA research team drank tea at various khaja ghars and talked to several of their owners. The owners talked about how it was challenging to run their businesses, due to high costs and rental rates. Rates can be around NPR 15,000 (USD $113), which is high, due to the street’s location near the bus park. Whilst the proximity to the bus park does bring passing trade, business owners struggle to balance operational costs because of high levels of competition in the area and because trade has decreased in recent months. One owner told the research team that the number of domestic travellers had fallen because passports can now be processed at district level. This means that an extended stay in Kathmandu to apply for or renew a passport before migrating overseas is no longer necessary.

Khaja ghars often sell cheaper home-made varieties of alcohol illegally, making them a place where those dependent on alcohol might visit throughout the day. CLARISSA research with khaja ghar owners has shown that the sale of this type of alcohol can be important in keeping a khaja ghar going. The research team observed the significant number of alcohol consumers in the street. Early in the morning the research team saw one man vomiting in the street.

People who consume alcohol in khaja ghar street often later go to the dohori street. Male, age 16, research team

The sale of intimacy and sex in small-scale businesses

In this more residential street, these types of activity seem to be carried out quite discreetly, compared to the busier and more commercial street nearby. But the research team did still observe khaja ghars where sexual services were likely available:

The business had the name “Khaja Ghar” displayed, but when we went inside, we found that there was nothing available, no tea or any other items. Instead, they were employing girls for their business activities. Female, 50, business owner, research team

We saw a simple curtain partitioning the khaja ghar. I felt like they do sexual activities there. Female, 17, research team

I observed one woman throughout our observation going from one place to another. I think she is a sex worker. She has put makeup on, and I think that is to attract the customers. She looked like she was looking for people to talk to and seemed almost eager and anxious to have a conversation. Female, 33, business owner, research team

Yes, she looked serious, and a bit stressed as well. I saw her smoking a cigarette and a guy was accompanying her. Male, 16, research team

Two adult female members of the research team went into one of the khaja ghars and sat inside a partitioned area. Soon after they entered a male customer in his 30s approached the owner, gesturing towards them. The business owner shook his head, presumably communicating that the research team were not there to provide sexual services. By early evening, some of the young women and girls working in the khaja ghars were observed standing outside them, either cooking sekuwa meat outside on the barbeque or trying to attract customers.

In the Gongabu area, some khaja ghars are known to employ young women and girls as waitresses, who also sit and engage with guests, or, act as a platform for customers to arrange sexual services off-site or sometimes on the premises (e.g. in a partitioned room or cabin).

A cabin inside a khaja ghar gives customers some privacy despite the eatery’s small size

Children working in the street

The research team observed over 20 children working in the street between the ages of 12 and 17. They were employed in various establishments including barbers/hair salons, motorbike repair workshops, butchers and fruit shops. Nearly half of the children observed were employed in khaja ghars.

We could see more boys in sekuwa (cooking barbeque meat), saloons (barber shop), and (motor)bike workshops. In the khaja ghars, we saw girls cooking and boys at the counter. Female, 18, research team

Most of the khaja ghars had children working in them; most of the children were between the ages of 14 to 17. Those working were mostly girls. Male, 16, research team

The children observed within the khaja ghars had different roles. As well as working children, the research team observed children who were present in a non-working capacity, probably because a parent owned the business (these children are not included on our map as working children).

We can differentiate between the workers and relatives who are helping out by the activities they are involved in. We could see the owners caring for their own children, for example, grooming them, dressing them up for school, feeding them food; I felt workers are more involved in the work of the khaja ghar like sweeping and cleaning the shop. Female, age 18, research team

However, discussions with business owners and employees in the street revealed that those working in the khaja ghars could be owners’ relatives (including business owners’ own children). This is supported by other CLARISSA research which finds children often work in their own or extended families’ businesses.

Within the khaja ghars, children as young as 12 years old, were involved in tasks such as cutting and drying meat.

It is noticeable in khaja ghars that the owners do not inquire about employees’ ages and hire employees as needed. Male, age 16, research team

I also saw a girl between the ages of 14 to 17 cutting meat to make dried meat. There was a lot of dried meat above her gas stove. She wasn’t wearing any gloves, so I felt it was risky. She looked like she runs the khaja ghar herself as there were no other staff there. Male, age 16, research team

Because of the small size of the businesses, the child employee might be the only employee and therefore take on the responsibility of running the business when the business owner is absent. This can leave the teenagers working there exposed to sexual harassment, especially if female: in one khaja ghar where the research team took tea, the owner’s teenage daughter was running the khaja ghar alone when several young men in their early 20s entered the khaja ghar and were observed getting close and trying to talk suggestively with the teenager.

As discussed above, the discreet nature of these businesses made it difficult to determine what activities were taking place.

In Gongabu, the mindset of boys is negative. They ask for “Shitan” (a code word referring to girls available for sex). If the owner confirms, it means there is a 100% chance of finding girls available for sexual activities. Male, 16, Research team

The research team debated whether it was possible to infer from their observations whether the sexual exploitation of children was taking place or not within certain venues on the streets. While the business owner participants emphasised that wearing clothes like shorts, might be evidence of young female employees being used to market businesses and attract male customers, the child participants felt that wearing such clothing could just be because they are comfortable and practical, especially in hot weather compared with more traditional clothes. While it was difficult to determine specific places where sexual services are provided, with certainty, or understand explicitly what type of activity was offered, the research team agreed that the area is one where different forms of sexual activity are used to increase these small businesses’ profits. These actions are carried out in discreet and varied ways, and utilised as a strategy to maximise profits in a competitive and challenging market:

The owners hire girls as a last resort to boost their business and increase sales. It was also noted that boys and men are often at the counter, but females are involved in serving customers. Female, age 34, business owner, research team

I have been in the khaja ghar business for the past seven years. I have heard that sex work happens in khaja ghars though we haven’t been doing it in our venue. I saw vast differences between other khaja ghars and my own business during our observations. The perception of businesses in Gongabu is quite bad, especially of khaja ghars, and even those that aren’t engaged in such (illicit) business have to bear the shame. Female, age 35, business owner, research team

The streets’ proximity to the Ring Road and bus park has led to the area rapidly developing to capture the domestic traveller market.

The neighbourhood mapping process

In spring 2023, a participatory neighborhood mapping was undertaken by twelve children aged 15 to 18, who had either worked or were currently working in establishments associated with the adult entertainment sector in Nepal (dance bars, dohoris, khaja ghars, or massage parlours), along with four business owners running khaja ghars in Gongabu. This initiative was conducted in collaboration with CLARISSA researchers and practitioners from WOFOWON, an organisation in Gongabu that has provided support to the CLARISSA programme.

Gongabu, located in the north of Kathmandu, serves as the city’s primary transportation hub. CLARISSA researchers had previously conducted scoping visits to the area and had selected a specific section of a street in Gongabu that comprised primarily of small-scale businesses such as khaja ghars. The chosen street segment was deemed representative of the surrounding streets in the area, with many khaja ghars catering to travellers entering and leaving the city.

The CLARISSA research team mapped and observed the business landscape and the activities in the street. The research team made their observations from street level but the relatively open and accessible nature of the businesses along the roadside meant that at times, members of the research team (children were always accompanied by adults) entered businesses to take refreshments. During these times, the team engaged with the business owner and/or employees working in the establishments.

During the first field visit, the research team worked in two groups to map each side of the street. To do this without drawing attention to themselves, they used mobile phones to take pictures and made audio recordings where they described the buildings. Following this visit, the two groups worked to create a base map in a workshop setting, reconstructing it using their detailed documentation from the field visit.

During the second field visit, children and business owners observed working children over the course of two days (between 9am and 9pm). They recorded working children’s ages, where they worked, the type of work or activity they were undertaking and the risks they were exposed to. Observations were again mostly made from street level by making notes or audio recordings on mobile phones.

In a second workshop, children and business owners worked together to refine their base map and record their observations onto it with the support of researchers and an illustrator. A third validation workshop was then held to check the detail of the maps. It was also an opportunity for the children and business owners to reflect on their overall experiences and discuss the observations.