Gongabu: working children engage in providing food and drink, entertainment and intimacy for travellers passing through

Gongabu is an area in the north of Kathmandu that is home to the capital’s largest bus park. The bus park is both a local and regional terminus, making the area a transport hub for those living in the city and a gateway for individuals traveling from the districts of Nepal to migrate overseas or to visit Kathmandu. The bus park is situated close to the Ring Road – the capital’s highway that circles the city and runs through the centre of Gongabu.

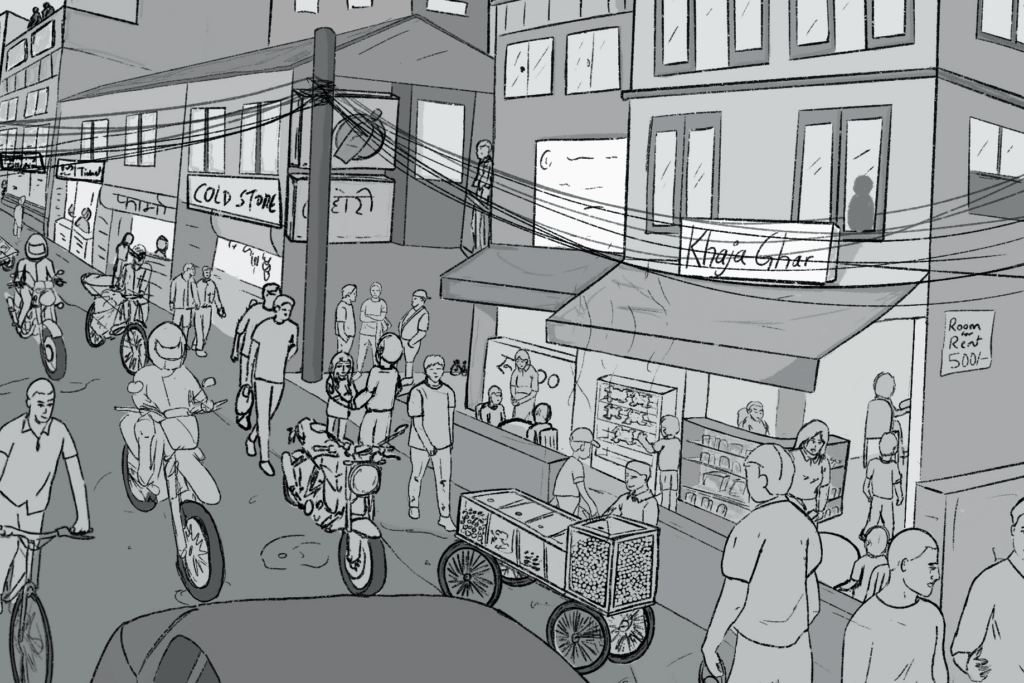

The Gongabu street selected for neighbourhood mapping is close to Kathmandu’s main bus park. It is hectic and polluted. The street is full of people looking for a place to stay, something to eat or some form of entertainment.

Gongabu is an area of haphazard and rapid development, where businesses have been rapidly set up in response to the establishment of the bus park, the capital’s main road transport hub, over the last 10 to 15 years. A feature of the Gongabu area is the high number of small-scale and highly informal businesses that co-exist with larger-scale businesses. Leading off from both sides of the Ring Road, multiple streets cater to the needs of those passing through, whether for a few hours, a few days or for a longer stay. While the larger streets run north to south from the ring road and contain a mixture of businesses, from small-scale eateries, pharmacies and sweet shops to larger guest houses and entertainment venues, a multitude of narrow thoroughfares run between them, each lined with khaja ghars (snack shops), small guest houses and other informal businesses.

The Ring Road is lined with guest houses, hotels and restaurants serving those traveling to Kathmandu from the districts of Nepal. Some will travel onwards to take up work overseas.

Sounds of the street

More sounds of the street

The area is crowded, and noisy and polluted due to the heavy traffic on the Ring Road. As well as being impacted by vehicle pollution, the surrounding streets feel dusty and smoky due to open fires used to prepare snacks, such as roasted sweetcorn and sekuwa (barbequed meat). While Kathmandu is a city with generally poor air quality, Gongabu feels particularly polluted, with dust particles and smoke clearly visible in the air.

In 2023, over the course of two days, a team of CLARISSA researchers, including child researchers, spent two days mapping one street in Gongabu and observing children that they saw working on the street. They recorded the children’s age, the type of work they were undertaking and the risks they were exposed to.

The Gongabu street mapped by CLARISSA runs from north to south, parallel to the bus park, with the northern end adjoining the Ring Road. The street is lined with three to five storey buildings and the road is busy with taxis, vehicles and pedestrians.

Map key

-

Girl

-

Boy

-

Girl

-

Boy

-

Street food vendor

-

Alcohol vendor

-

Goods delivery rickshaw

-

Vegetable vendor

-

Barbecued sweetcorn vendor

-

Samosa vendor

-

Shoe repair/ cobbler

-

Taxi

-

Rickshaw taxi

-

Motorbike taxi

-

Guest house/Hotel

-

Restaurant (incl. coffee shop, fast food)

-

Khaja Ghar (snack shop)

-

Dohori (folk dance bar)

-

Massage parlour

-

Dance bar

-

Pool house

-

Travel agent

-

Bus ticket agent

-

Currency exchange

-

Trekking agent

-

Convenience store

-

Clothing shop

-

Bakery

-

Butcher

-

Sweet shop

-

Pharmacy

-

Fancy goods shop

-

Toy shop

-

Liquor shop

-

Fruit shop

-

Mechanic

-

Photo shop/studio

-

Bank

-

Phone repair shop

-

Hairdresser

-

Spiritual services

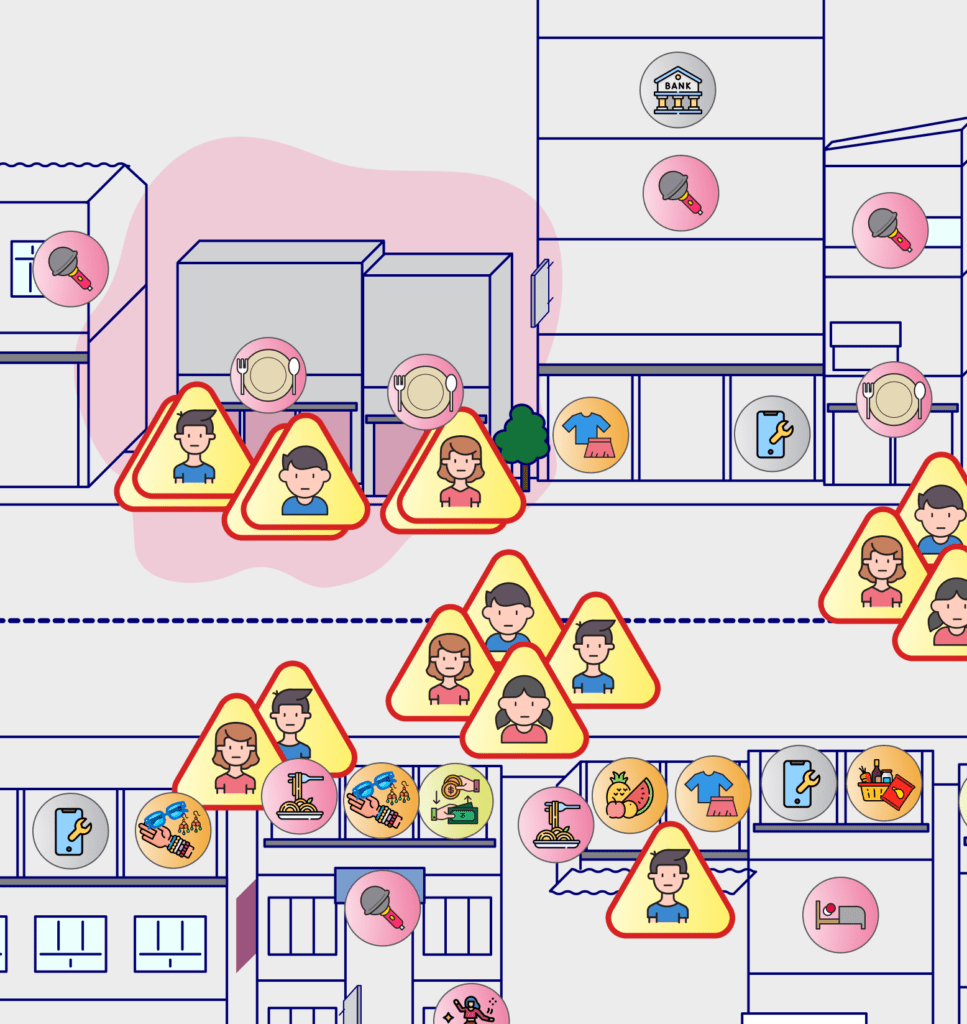

A digitalised version of a map created by children and business owners of a street that was observed and documented in detail by a CLARISSA research team, with a particular focus on mapping child labour

The map developed by the research team (made up of eight children and four business owners working in the adult entertainment sector, along with CLARISSA researchers and members of a local partner organisation who provided support) shows that the 150-metre section of street contains over 90 businesses including small-scale pharmacies, khaja ghars (informal eateries), grocery shops, sweet shops, clothes shops and medium-scale businesses such as guest houses and restaurants. The area also has a high concentration of night entertainment venues: there are eight dohoris (folk music and dancing venues) and one dance bar on the 150m stretch of road.

The map shows where the research team saw children working on the 150 metre section of the road. Over 40 children were seen working either in businesses or on the street during the observation period.

The street

Children and business owners (comprising part of the CLARISSA research team, and with previous involvement in other CLARISSA participatory processes) observed the street between 9am and 9pm on a Friday and Saturday in May 2023.

The street was busy from early in the morning with travellers sitting in restaurants and khaja ghars drinking tea and having breakfast, and then later with people shopping or wandering around.

The research team observed a range of business activities happening on the street, including street food carts selling vegetables, roasted corn, paani puri and chatpati (street food); individuals walking the streets selling food such as samosa and curry from buckets; street sellers offering a range of goods including gold plated jewellery, clothing, or flutes; and cobblers sitting on the road to mend or clean shoes. A pandit (holy man) travelled up and down the street collecting alms and providing tika (a blessing).

Motorbike and car taxis lined the street, sometimes disturbing the flow of traffic as they partially blocked the road. Sometimes confrontations erupted between different types of sellers co-existing in a congested space:

We observed many things. One thing that we observed, and I didn’t like, was the taxi driver giving troubles to the street vendors. Taxi drivers were picking up fruit from the cart of the fruit seller without paying any money. On top of that, taxi drivers were misbehaving with the fruit sellers.

Female, age 50, business owner, research team

Footpaths on the street are crowded as taxis, pedestrians and street sellers wrestle for space

The street vendors and high number of pedestrians made the footpaths of this street difficult to navigate:

The road was congested and even if there was a footpath it was difficult to walk on it as many shops extended onto the footpath

Female, age 33, business owner, research team

In addition, at the south end of the street, the research team observed that a steady stream of people flowed from an exit gate from the bus park.

The street over the course of the day

In the morning, there were some women and girls shopping on the street. However by late afternoon approximately 90% of those walking in the street or dining in the restaurants and khaja ghars were men. It was common to only see women and girls serving in the restaurants rather than dining in them:

We saw males more in evenings. Most of the visitors were male. Women were very few. Women don’t come to visit this place in the evening. Only those girls who work in nearby places were there.

Female, age 17, research team

Customers in restaurants were mostly aged between 20 and 50 years old, but groups of young men in their 20s and 30s were also prevalent. The research team thought that these were probably groups of men travelling together to work overseas.

As the day continued the street became busier and more frenetic. By early evening, numerous touts could be seen on the street:

When the evening starts many people come out to market their business, such as restaurants, guesthouses and tickets for the bus

Male, age 17, research team

The night entertainment venues on the upper floors of buildings opened their shutters at around 7.30pm and employees from these venues began standing on the street, trying to attract customers.

Touts on the street of Gongabu refer visitors to guest houses, hotels and restaurants

Children working in the street

Children were observed working in shops or selling products or food stuffs door-to-door. Children the research team observed selling included: a girl aged around 16 who was working in a kitchen utensil shop; a group of three teenagers aged between 14 and 17 selling marketing products on the street; and a child selling coconuts. Many more children were seen working in businesses associated with the hospitality industry, including restaurants and khaja ghars:

I saw a 14 to 17-year-old boy bringing tea to different shops on a tray, he worked in a restaurant

Female, age 33, business owner, research team

In two small-to-medium sized restaurants the research team saw numerous staff in their mid-teens (see ‘The Building’ section below).

I also saw a few girls, three, between the age of 14 and 17 walking on the street. I think they work in a dohori because their clothing is short and revealing, but not expensive looking. I worked in a dohori before and I am 100% sure that they work in a dohori Male, age 17, research team

Three girls aged around 17 wearing the same outfit were seen outside a dance bar, trying to persuade a customer to enter. Another girl of around 17 years of age was seen outside a dohori inviting passers-by to enter. A teenage boy was working as a tout, trying to refer customers to one of the nearby restaurants and guest house.

The research team, also noticed that some children were involved in arranging sexual services directly with customers. These exchanges were discreet, and the hidden nature of the activity meant that the children and business owners in the CLARISSA research team relied on their own knowledge of the context to understand what was taking place. Numerous incidents were noticed, for example girls aged 16 or 17 were meeting customers outside guest houses or standing next to guest houses negotiating rates for sexual services.

Teenage girls were seen meeting customers or making arrangements to provide sexual services.

Facilitating the provision of sexual services

Aspects of the street seemed to facilitate the sex industry. The research team noticed that pharmacies on the street were very small with few medicines available but had condoms displayed in cases at the front of their counters.

I found that that there were a lot of medical shops and I believe they care about protection. So, they sell contraceptive products. They sell other products in the morning but in the evenings, they sell condoms and such things more. Female, age 17, research team

Those agents who come to advertise the business also make deals about the girls. Those agents are also under 18. Girls don’t come to bargain because of the fear that police might arrest them, and they can’t run away as fast. Male, age 16, research team

In the evening, young people working on the street congregated around street food and drink vendors. Numerous employees from night entertainment venues were seen eating chatpati (dried instant noodles served with spices) from the street stalls.

I felt the riskiest work was girls going to dohori without eating and just having Chatpati. It can have adverse effects on their health in the long term. Usually, girls working in dohoris have to drink alcohol to attract customers to spend more there. So, alcohol and bad food can have adverse effects on their health. Usually, they go home drunk. Female, age 17, research team

The research team observed several girls, aged between 15 and 18, gathered around a woman with large thermoses.

On the first day we saw girls drinking tea with Chatpati which was an odd combination, so I was suspicious. The next time I saw it was alcohol because of the smell and its white colour. Female, age 17, Research team

Children from the research team’s experiences in the street

Generally, the children making up the research team felt that this street and general area was risky and, despite being accompanied by adult CLARISSA research team members at all times, they described feeling fearful when walking in the street. Several felt that they might be being followed.

Girls in the research team felt particularly vulnerable and described sexual harassment experienced in the street:

There was a sense of fear as we realised the disadvantages of being female, as we were verbally teased and asked for our telephone numbers.

Female, age 18, research team

As well as experiencing sexual harassment themselves, they also noticed other girls of a similar age being subjected to the same behaviour on the street, for example:

The boys were teasing two girls aged below 17 who were going to eat snacks at a sweet shop.

Female, age 18, research team

Despite the presence of adult CLARISSA researchers, child researchers were approached in the street by a range of men and asked ‘to go’ (i.e. propositioned to provide sexual services)

In the evening on (that) street, adult individuals, even including government staff (wearing uniform), approached me, asking if I would engage in sexual activities. Some young boys teased me by singing songs. I was dressed modestly in a simple kurta, and they may have assumed I was innocent and naive. It feels like if they see a girl who is new or appears naive, they may try to take advantage of her.

Female, age 18, research team

I realized the negative sides of being a girl. My experience was different to that of the boys in the research team. People were flirting with me. They came close. They touched me. Flirted and spoke bad words to me. I felt I got quite different treatment than my male counterparts did. I felt quite uncomfortable.

Female, age 17, research team

Reflecting on the experience of the girls in the research team, one child expressed surprise at how overtly sexual services were solicited on the street:

We used to hear that the bus park area is the red-light area of Nepal; now observing people actively engaged in sex related work, now I know it is really the case. If you stand for a bit people, come to you asking, will you go?

Male, age 17, research team

Child members of the research team speculated on the reasons why girls dressed simply were targeted:

Better dressed girls can defend themselves and are more talkative so people avoid them and choose to find girls who are dressed simply and look new to the city.

Male, age 17, research team

The building

Eight children (three boys and five girls) were working in the restaurant on the ground floor of the building. The customers were primarily men.

Participants were asked to focus on one building that represented a high prevalence of child labour in the street. A three-storey building in the centre of the street was selected. The building was surrounded by four dohoris.

The ground floor of the building had signs advertising the types of food and services on offer, which includes rooms for rent for 500 rupees (less than $4 USD) per night which is inexpensive compared to guest houses and hotels. Awnings cover an area outside where, during the observations, an (adult) was cooking with a large oven.

The décor inside the restaurant was simple and hygiene standards were low. The main dining room had around five tables but there was a smaller, more private dining room behind the main dining room and another on the floor above. On the first floor there were also numbered doors with padlocks, which were the rooms that could be rented for a night. There was one shared toilet which had not been cleaned. Because of the low price and lack of facilities offered, members of the research team suspected that these rooms might be used specifically for sex work:

I think that the khaja ghar also has a guesthouse. There were a lot of young girls and boys between the ages of 14 and 17. I went up to the floor with (a CLARISSA researcher) and we saw many rooms and I also smelled a strong smoke smell there. They might be running sex business there.

Male, age 16, research team

The restaurant was busy by the afternoon, and as with many of the restaurants on the street, most of the customers were men.

Children and business owners chose the building highlighted in pink to represent child labour in the street. The building houses a small restaurant on the bottom floor and rooms above which can be rented for the night. The restaurant is close to four dohoris (depicted by a microphone symbol).

Children observed working in the restaurant

Participants counted three boys and five girls working in the restaurant and estimated their ages to be between 14 and 17. The cook was the only adult who could be seen working there.

Teenage girls serve customers in a restaurant. In the evening, the research team observed that they had changed their clothes and were going to work in a dohori close by

The restaurant’s relationship with other businesses

Participants saw the restaurant supplying khaja (snacks) to the nearest dance bar and dohori. Child participants also observed teenaged girls working in the small restaurant changing their dress and going to work in the nearby dohori.

Dohoris serve spicy food and alcohol. They order food from (the restaurant) and the girls working (there) might also work at the dohori as they wore cultural dress and heavy makeup and went out after 8pm. I saw them enter [dohori name]. So, the girls were working two shifts: khaja ghar in morning and dohori in the evening. The girls were between 15 to 17 years old.

Female, age 17, research team

Discussion

What is striking about this street in Kathmandu is the amount of child labour that is clearly visible even when observing from street-level and not entering many of the buildings. Due to safeguarding concerns the research team were unable to observe establishments on floors above ground level such as dance bars, dohoris and guest houses but children associated with these venues could still be seen trying to garner custom on the street, or spending time eating or drinking before or during their shifts. While over 40 children were observed working in this 150-metre section of street on one day, it is likely that the actual number of working children is far greater than those observed during the mapping process.

Also significant was the visibility of negotiations related to forms of sexual services, including by those in their mid-teens. The street is a site of opportunistic and transient connections that serve the needs of a predominantly male clientele, including those for sexual activity with young women and girls. While touts might also be involved in brokering arrangements (including touts who are children), the looseness and openness of negotiations is notable. Transient trade, a high volume of customers and the area’s association with the sex industry, results in an environment where sexual services can be solicited opportunistically in the street itself. Sexual services were even sought via passing encounters:

In Gongabu if a girl stands in the same place for a long time, then a male will ask jaane ho (shall we go)? That’s my learning from the observation.

Male, age 17, research team

As a result, there are few, if any, spaces for young women and girls on this street to be free from male demands for intimacy and their experience is wholly shaped by a perception that they are sexually available. Markedly, those who looked young and ‘simple’ were targeted; this preference for girls not associated with the sex industry rendering younger adolescents more vulnerable to harassment.

More broadly, child labour is both normalised in this neighbourhood and relied upon to keep businesses going – to the extent that there were establishments which seemed to be run almost entirely by adolescents. Accompanying CLARISSA research shows that the critical role children play within businesses is not usually reflected in their pay; age-based pay-differentials, where children are paid less than their adult counterparts, are common as are very low salaries. It is notable that in the restaurant the research team focused on, the teenage girls working there were working two jobs – in the restaurant and then in the dohori. Low wages can put pressure on children to engage in or transition into roles where they are vulnerable to sexual exploitation; for example, in night-entertainment venues where earnings are largely dependent on tips and commission, which often involves engaging in sexualised interactions with customers (e.g. kissing, sexualised touching). . Transitions between different types of businesses are facilitated by the proximity of venues in these streets – in this instance, a short walk to the dohori or dance bar next door provides additional earning opportunities, as well as a different/accompanying set of risks and an extremely long working day.

In addition to children moving between businesses, there is evidence of multiple interconnections between businesses that enable profit to be made from those passing through, and that allow for these businesses to function. For example, the small restaurant mentioned above works in conjunction with the dohori and dance bar nearby, the street-food sellers provide cheap alcohol and food to night entertainment workers, night entertainment venues provide customers for guest houses / rooms for short-term rent, pharmacies provide protection for sexual encounters. Larger-scale, more formal businesses are often supported by a plethora of informal businesses, both to meet the needs of their customers and employees at low-cost.

CLARISSA’s observations within businesses associated with the adult entertainment sector provide insights into the experience of work within these types of venue [Link to work shadowing case studies (if possible)]. But the street mapping process reveals the additional demands on those working in the neighbourhood, including children. The research team noted the poor diets and eating habits of the female employees working in dohoris and dance bars who rely on unhealthy snacks from street-sellers, and the prevalence of homemade alcohol vendors which points to the risk of alcohol addiction associated with working in the entertainment sector. The neighbourhood is a demanding one to work in – it is polluted, noisy and crowded and for teenage girls, it is a neighbourhood that they are unable to navigate without being repeatedly subjected to sexual harassment.

CLARISSA neighbourhood mapping

CLARISSA neighbourhood mapping sought to understand children’s experience of urban neighbourhoods and identify the characteristics of urban neighbourhoods that contribute to the emergence and perpetuation of Worst Forms of Child Labour. Gongabu was chosen as it is one of Kathmandu’s major transport hubs and as a point of departure for migrant labourers traveling to or returning from overseas, the area is known for providing this transient population with a range of services and entertainment, including the provision of sex-related services and therefore is a focus of WFCL.

Our research team comprised eight children aged from 15 to 18 (two boys and six girls) who had worked or were working in venues associated with the adult entertainment sector in Kathmandu (dance bars, dohoris, khaja ghars or massage parlours), and four women who had run khaja ghars in the area, plus CLARISSA researchers. They undertook a participatory neighbourhood mapping involving scoping visits which led to a portion (c. 150m) of this street in Gongabu being selected to be mapped. The section of the street was chosen because it seemed representative of a busy commercial street in Gongabu which offers night entertainment alongside a range of other services (guest houses, restaurants fancy goods etc) for those traveling in and out of the city.

CLARISSA researchers (with support from a local partner organisation, WOFOWON), accompanied the business owners and child participants on two field visits to map and observe the business landscape and the activities in the street. The research team made their observations from street level.

During the first field visit, children and business owners worked in two groups to map each side of the street. To do this without drawing attention to themselves, they used mobile phones to take pictures and made audio recordings where they described the buildings. Following this visit, the two groups worked to create a base map in a workshop setting, reconstructing it using their detailed documentation from the field visit.

In the second field visit, the children and business owners in the research team observed working children over the course of one day (between 9am and 9pm). They recorded: working children’s age; where they worked; the type of work or activity they were undertaking; and the risks they were exposed to. Observations were again mostly made from street level by making notes or audio recordings on mobile phones.

Observations were recorded on base maps which were then digitalised by the illustrator.

In a second workshop, the children and business owners in the research team worked together to refine the base map and record their observations onto it with the support of CLARISSA researcher team members and the illustrator. A third validation workshop was then held to check the detail of the maps. This was also an opportunity for the children and business owners to reflect on their overall experiences and discuss the observations.