Living among leather factories

A story of a building and its residents in Gojmohol, Hazaribagh

In this building there are factories like gloves, shoes, dice, can-making factories. Moreover, there are several leather related factories where leather is cut, sewn and coloured. Child Researcher, 16

About the building

This is the story of a well-known residential building on the 30 Feet Road in the Gojmohol neighbourhood of Hazaribagh in the capital city of Dhaka in Bangladesh. The multi-functional building is owned by a businessperson who holds significant influence in the area. It comprises living and commercial units. Located near the’ Khalpar’ area, a dirty water and waste channel, the smell of contaminated water and odours from nearby leather factories permeates the building.

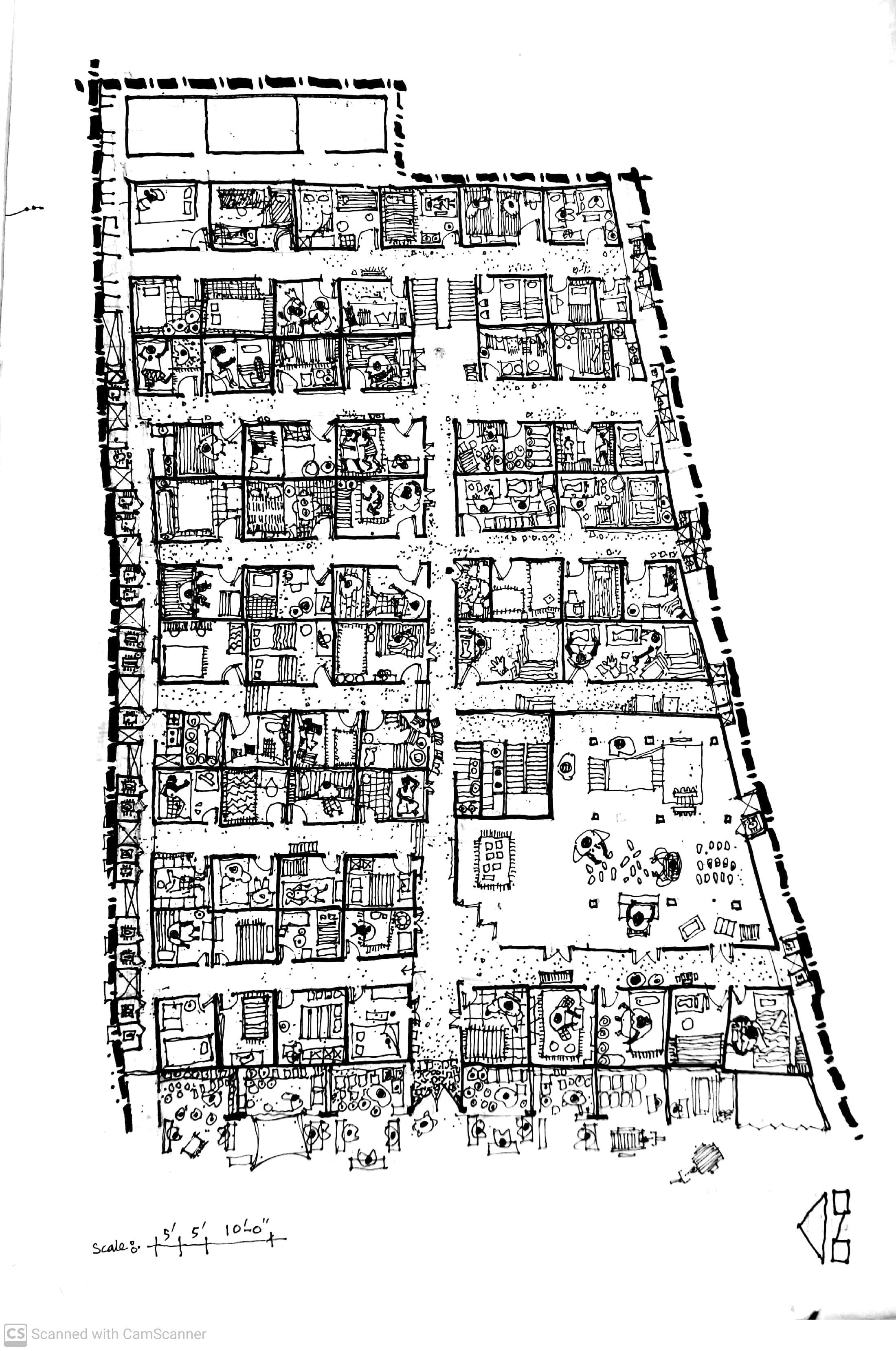

On 26 July 2023, two boys (16 and 17 years old) along with an adult research assistant conducted observations of the building for a total of five hours, over three time periods to capture the living conditions and lived experience of residents. The floor plan for each story of the building was drawn by illustrator and the observation notes, photos and videos were analysed by the CLARISSA research team and the children, before the main findings were compiled into this account.

Due to the heat in their rooms people are sitting in the entrance to the building.

Home to 177 households, the building is organized into many different rooms over two floors. The rooms mostly measure approximately 2.5 metres in width and 3 metres in length. In an extended part of the building, the rooms are smaller, and therefore cheaper. Most of these rooms are home to families of five to six people, although some of these rooms are rented out as small-scale leather factories. Rents vary quite significantly according to room size, ranging from BDT 1500- 4500 (USD $15 to $45) a month. Some rooms bear the signs of recent plastering, while others wear the shabbiness of time. Everyone shares communal areas such as kitchens, bathrooms and corridors.

The building has two floors constructed out of cement and a roof top, where another 15-20 residential rooms have been made out of tin.

A factory located inside the building

The ground floor

The ground floor is a mixture of residential business units (there are six leather-related businesses arranged within a dedicated area). It is a beehive of activity, with skilled craftspeople and energetic child apprentices working tirelessly. A shoe factory stands out as one of the larger and dynamic establishments in the building. At the time that the CLARISSA research team visited, a rickshaw loaded with leather rags pulled up to the entrance of the building. This shows how much the leather industry is penetrating a building which is home to a great many children.

The rest of the floor is organised into small square and rectangular living quarters (rooms), separated by dark corridors. Few of these rooms have access to windows and natural light. All families living in these residential units share a communal kitchen.

The layout of the ground floor of the building.

The first floor

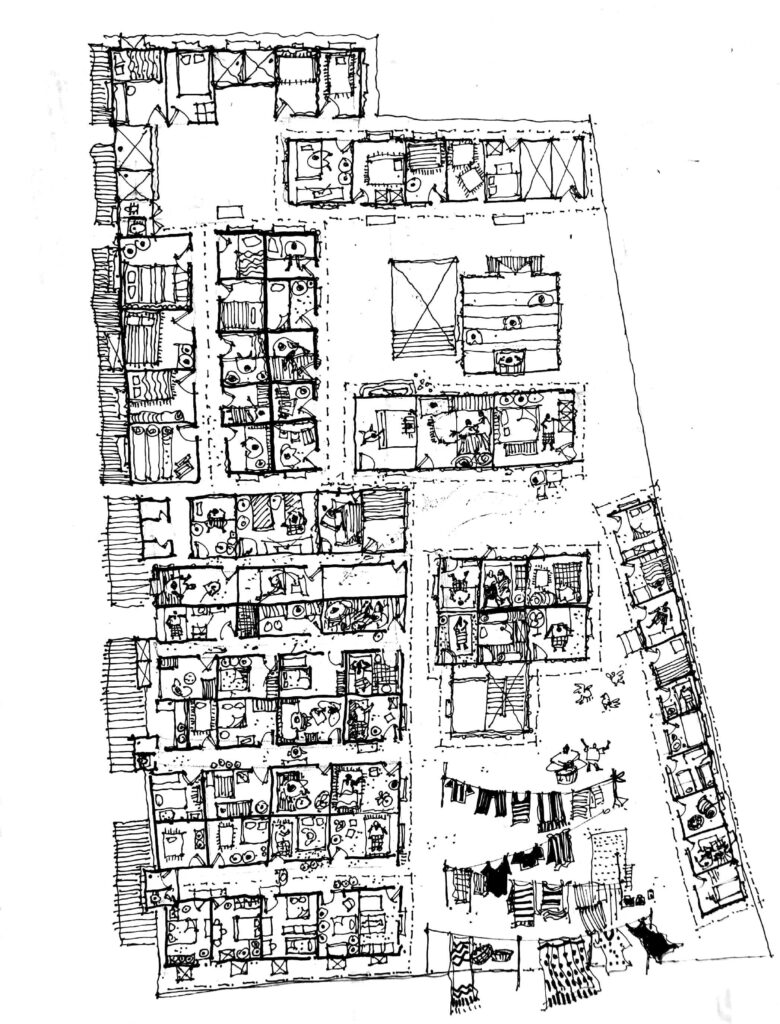

The first floor is predominantly residential, with no commercial units. The floorplan illustrates how the building is organised into small living quarters for families.

Holes have been made in some ceilings to ventilate them and cool them down. The problem is that these holes also let in rain.

As well as a communal kitchen and bathroom for all the families to share there is also an NGO-run school and a mosque on this floor. There is also an open terrace (which has no barriers or railings around it to protect people from falling from the rooftop.)

The layout of the first floor of the building.

The rooftop

The rooftop is an open space, although another 15-20 makeshift rooms (dwellings) have been made. These rooms have natural light, but their construction is not advanced. They are constructed from tin, which makes the rooms very hot and the area outside is prone to flooding when it rains.

The rooftop is the only significant open communal space within the building, so it is an area used by adults to socialize in and children to play in. Children and teenagers also play in corridors throughout the building and outside the entrance to the building.

There is a kitchen on the rooftop, but it has no lights. Residents improvise by using light from their mobile phones to see whilst they cook.

Some of the dwellings on the rooftop

Life in the building

Living spaces and communal areas are cramped and overcrowded in this building. As it is mainly families with children who occupy the building it feels busy and vibrant. Surrounded by small tea stalls and stores, the building is in a bustling area where people from various occupations gather and chat. The research team arrived at the building at 9.30 am to begin their observations and many of the building’s residents were seen buying breakfast and tea outside. Street vendors were also entering the building to sell food to residents, illustrating how life in the building spills onto the street and how life on the street spills into the building.

During the daytime, people were observed working, cooking and doing chores. In an interesting reversal of traditional gender roles men were observed washing clothes, cooking meals, and caring for children. Many of the women were absent as they were working outside the home. Living spaces have been turned into small leather factories, and parents, including fathers, were observed juggling childcare and work.

As the clock ticked past noon, several children gathered to watch cartoons in a ground-floor household. Many schoolgirls returned home in their uniforms, their laughter and chatter filling the building. Boys in school attire were a rare sight, suggesting different paths for boys and girls. Mothers bathed their young children who had just returned from outdoor play, their faces adorned with the evidence of their adventures. Some older children, (aged between ten and 17), arrived home from working at nearby factories, taking a break to enjoy a meal.

Women cooking in a communal kitchen in the building.

Some of my known boys who work nearby leather factories are also returning after their shifts. They are aged around 15-17 years old. Among the dwellers, I have seen some of them are getting ready for their office or factories. They work in the night shifts.

Child researcher

Women gathered outside their homes, sharing stories and experiences of their day. Children, now bursting with energy, played on the rooftop, their mothers watching over them. Fathers joined in with the fun, bonding with their children through play. Teenage boys found their social hub in the dimly lit staircases and corridors. Some smoked, others gossiped, and a few played video games.

It was quiet in the evening despite the large concentration of families. Given how difficult it had been to sleep in the heat the evening before, people took the opportunity to rest. The sky darkened with clouds and the building cooled a little.

This building faces numerous challenges, including heat and poor ventilation, poor lighting, wet and slippery floors, rooftop safety issues and security problems. A lack of proper waste management contributes to an unhygienic environment, putting the residents’ health at risk. Below are some overarching observations made by the CLARISSA research team.

Some residents peak into a neighbour’s room to watch TV.

Woman working outside due to suffocating heat inside her tin room on the rooftop.

Heat and poor ventilation

The rooftop section of the building is much hotter than the first floor.

The heat is made worse by poor ventilation throughout the building. Some rooms lack windows, relying on doors for ventilation. Throughout the building the air is stagnant. Drying clothes fill up the corridors. The research team saw a woman hanging out wet clothes in the corridor next to clothes that where already drying, suggesting the use of corridors as makeshift verandas.

The heat is directly pouring into the tin dwellings on the rooftop floor. The temperature is around 32 degrees Celsius though according to the weather update it feels like 36 degrees Celsius. Adult Researcher

Water supply issues

Not all residents have water supplied to their room. Some collect water from communal taps that had not been cleaned for months or even years. The once-silver taps have faded to a grimy black. Residents use various containers, from silver pitchers to large cooking pots, to collect water from a tap.

Filling water from a communal tap

Dark corridors

Dim, inadequate lighting throughout the building creates a gloomy atmosphere, and the first floor’s corridors are shrouded in darkness even at 10 am.

Inadequate lighting is posing safety hazards and makes navigation through the building difficult. It’s quite tough for me to walk without the help of my phone’s torchlight but it seems quite normal for the children and people of this building as they are moving without any problems. Adult Researcher

A dark corridor on the ground floor is lined with overflowing rubbish bins

Holes in the walls of the bathroom contribute to sexual harassment of girls.

The bathrooms in the building are unclean and in a state of disrepair, rendering most of them unusable. Broken taps add to the residents’ problems, wasting water continuously, and causing slippery floors and accidents. One researcher heard from residents that:

A similar case happened to one of the elderly ladies among the dwellers. The lady was sick and physically unstable. She slipped on the wet and slippery floor of the washroom and injured herself gravely. Though the people around here are more likely victim-blaming the lady by saying that she should have been careful, it’s quite normal for the washrooms to be slippery and covered with water. They were saying that “Why would she go to the washroom alone if she were sick? She had to watch where she stepped. It’s normal that the washroom would be covered with water.

One of the adult researchers noted that a simple system to turn off the water tank when full could save water and provide a valuable resource for the residents.

The bathrooms present a particular risk to girls as many of them report experiencing harassment,:

There were also incidents like a girl was followed through the gap of the bathroom door and was harassed, when I used to live here.

Child researcher, 17 years of age

In the evening the bathrooms are shrouded in darkness and foul odours deter anyone from approaching them.

Wet and slippery floors

Rainwater seeps in through ventilation gaps, rendering the floors throughout the building wet and slippery. The rooftop becomes waterlogged, preventing children from playing freely. A suggestion was made by the research team for the landlord to repair the drainage system, so rainwater could be efficiently channeled away.

You see, water always gets clogged here, I have asked the manager to do something about it, but he is very reluctant, I go to work, and my child plays here the whole day in this dirty water, at the end of the month, all my money goes into medical expenses. Female resident

The research team observed a woman struggling to keep her room dry for her children.

Unattended children

The dangers created by rooftops and other environmental hazards are amplified by the number of children who are unattended throughout the day. This is testament to the number of parents – both mothers and fathers – who leave the building to work. Unattended children spend the majority of the time that they are unattended doing things as they like. Small children were seen eating off a dirty concrete floor. Teenage boys took turns to jump from high corners of the staircases. Without any protective railings around the roof or staircases, serious injuries from falling are a constant risk. Recognizing the danger, residents have pleaded (as yet to no avail) for immediate installation of railings to ensure the safety of their children.

An unattended child eating rice from the floor

One area of particular concern to the CLARISSA research team was the entrance floor, which, although uneven, serves as a playground for the children. On one occasion, a young child was seen to lose their footing, tumbling in front of a concerned researcher.

A young disabled girl, aged around 9-12 years old, was observed sitting on a worn-out baby pram under the scorching sun. Her thin, malnourished body bore the scars of neglect. With twisted limbs and an inability to speak, she sat drenched in sweat.

As the day transitioned into evening, the child in the picture remained outside in the pushchair, it seemed that she was deliberately left there by her family to attract the attention of our team, and /or NGOs and institutions that could potentially help her. Another mother discussed how she was contemplating taking her child to a traditional healer, she was exploring all avenues for her child’s well-being. In this tightly knit yet troubled community, daily life seems to be an unending struggle against poor hygiene, inadequate living conditions, and a continuous battle for survival.

An unattended child with physical disabilities.

A child labourer

Leather work in the building

The ground floor of the building is a hub for leather-related businesses – a cacophony of sewing machines, cutting tools, and stacks of leather. Three factories are dedicated to the intricate art of sewing leather into various products, while two other factories focus on cutting leather into precise shapes. In one room, leather lay stacked high, accompanied by containers filled with different chemicals, which the researchers assumed are used to treat and dye leather.

Discussion

The story of this building reveals both the resilience and the hardships faced by its inhabitants. It brings together multi-generational work, living, education, recreation, and worship, creating a social vibrancy and severely compromised living conditions. The residents, particularly the children, face numerous hazards and safety concerns that warrant urgent attention.

Painting a vivid and unfiltered portrait of life in Hazaribagh’s historic leather neighbourhood, the story of this one building reveals some surprising realities. The penetration of a hazardous industry (leather) into the homes of children is particularly striking. The children living in this building are growing up around children and adults working with lasers, blades and amongst chemicals without safety precautions. Through its mixed-use, multi-purpose function the building is creating the learned experience that children in hazardous work is a normal part of growing up.

Girls living in this building are more likely to go to school than boys. Boys are more likely to work. Researchers observed a reversal of traditional gender roles in a lot of households. Women go to work and men step into child rearing roles, though the absence of both parents is still widely observed in the number of unattended children.

The building is privately owned, and maintenance is poor. Disrepair is a consequence of years of neglect and some residents have arranged their expectations accordingly – preferring to emphasise personal responsibility in accidents rather than assigning responsibility to the landlord. Even when residents have made the link between poor environmental conditions, poor health and household income spent on health issues, they have had little success in advocating for changes. As a consequence, cramped and compromised conditions have become part of everyday life. As one of the child researchers reflected on his involvement in the process:

We used to live here but didn’t pay much attention to the living condition of this place. We didn’t think much about the lack of light in the corridors and bathrooms or the railing of the rooftops, but today it appeared to be very important for the dwellers of this building

Child researcher

The child’s experience points to the capabilities of residents to adapt to their circumstances. One example of families adapting to poor infrastructure is eating from food vendors outside their home. With cooking facilities so limited, and gas supply irregular, it has become normal to eat out, but this strategy only works when households have the money to do so. In another piece of CLARISSA research, Stories of children’s days working children often report feeling hungry all morning. They go to work without food because cooking facilities at home are lacking. The building – and its visible state of disrepair – is amplifying the demanding, stressful and impoverished nature of the lives led by its occupants.

The building mapping process

The intention behind mapping residential buildings in the Gojmohol neighbourhood of Hazaribagh was to capture the living conditions and lived experience of residents. Child researchers and community mobilisers engaged by the CLARISSA programme selected this building for observation while they were mapping the 30 Feet Road. The 30 Feet Road is significant to the child research team as most live nearby and hang out close to the building. They were aware of children involved in telling Stories of Children’s Days who had pointed out unsafe features of the building. Three children from the Children Research Group live in the building which granted the research team access.

Following a one-day workshop to practice observation methods and effective recording techniques (including note writing, audio recordings, videos and photos), as well as develop safeguarding and consent plans, the children proposed suitable observation times.

On 26th July 2023, two boys (16 and 17 years old) along with an adult research assistant conducted observations of the building for a total of five hours, over three time periods. The children proposed 9:30 AM to 11:30 AM, believing it to be a time for various activities in the building, 1:00 PM to 2:00 PM, aiming to capture the moment when workers returned for and 5:30 PM to 7:30 PM when all working people returned home. Observations were not continued after 7:30 PM due to safety concerns. The observers did not enter any rooms but were able to observe inside activities as the doors were often open.

The floor plan for each story of the building was drawn by illustrator Prof Sajid Bin Doza from the Department of Architecture at the State University of Bangladesh. Observations were analysed by the CLARISSA Thematic Research team, the children, and the research assistant who conducted a debriefing session the day after data collection. During this session, observers shared their overall experiences, discussed their observations in detail, and answered probing questions from the CLARISSA team. Detailed notes were compiled from these discussions.