Thamel: child labour in adult entertainment businesses in Kathmandu’s tourist district

Thamel is a popular commercial neighbourhood and a main hub for the tourism industry of Kathmandu. It is a square kilometre of restaurants, bars, cafes, trekking and tour agencies, massage parlours and shops that cater to the needs of international and domestic tourists, as well as Kathmandu residents seeking entertainment. Developed since the 1970s when it started to be used by western tourists, Thamel has become a place for (predominantly male) Kathmandu residents to transgress social norms related to sex, food and alcohol, particularly in the night entertainment venues that are now prevalent.

A street selected for participatory neighbourhood mapping represents the diverse business landscape of Thamel that caters to international and domestic tourists as well as locals seeking entertainment. Small-scale shops, restaurants and khaja ghars (snack shops) intermingle with higher-end hotels.

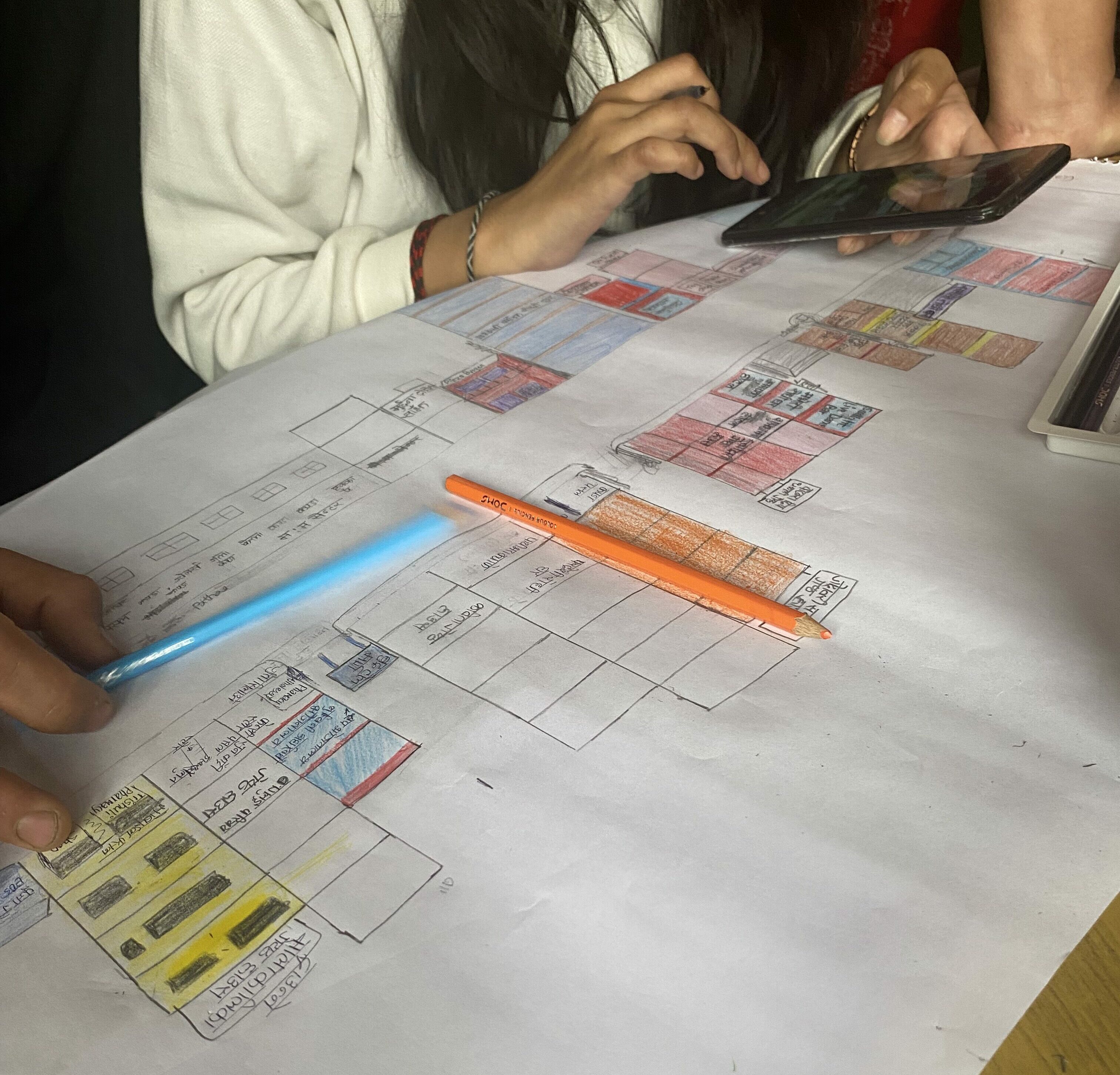

During spring 2023, eight children (one boy and seven girls) age 15 to 17 who had worked or still work in venues associated with the adult entertainment sector in Kathmandu and four business owners (three women and one man) who run massage parlours in Thamel, plus CLARISSA staff, formed a research team to undertake participatory neighbourhood mapping. The team mapped 150m of street and observed the business landscape and activities taking place in the street. A base map was drawn up and then, as the next part of the process, the team observed and recorded working children over the course of one day. They noted working children’s age, where they worked, the type of work or activity they were undertaking and the risks they were exposed to.

Map key

-

Girl

-

Boy

-

Girl

-

Boy

-

Street food vendor

-

Alcohol vendor

-

Goods delivery rickshaw

-

Vegetable vendor

-

Barbecued sweetcorn vendor

-

Samosa vendor

-

Shoe repair/ cobbler

-

Taxi

-

Rickshaw taxi

-

Motorbike taxi

-

Guest house/Hotel

-

Restaurant (incl. coffee shop, fast food)

-

Khaja Ghar (snack shop)

-

Dohori (folk dance bar)

-

Massage parlour

-

Dance bar

-

Pool house

-

Travel agent

-

Bus ticket agent

-

Currency exchange

-

Trekking agent

-

Convenience store

-

Clothing shop

-

Bakery

-

Butcher

-

Sweet shop

-

Pharmacy

-

Fancy goods shop

-

Toy shop

-

Liquor shop

-

Fruit shop

-

Mechanic

-

Photo shop/studio

-

Bank

-

Phone repair shop

-

Hairdresser

-

Spiritual services

Digitalised version of a map created by a CLARISSA research team. The street was mapped in detail and later the team and recorded where children were working on a single day in May 2023 and recorded this on the map.

The map developed by participants shows that the 150-metre section of street mapped has approximately 40 buildings housing more than 70 businesses. Businesses include a high-end hotel and restaurant, an ethical/fair-trade shop, a bank/ATM point, shops and services related to travel and tourism, Nepalese craft shops, restaurants of different scale serving various types of cuisine, small grocery shops, a dance bar, a dohori, khaja ghars (snack shops), food stalls and four massage parlours. Thamel is home to over 200 massage parlours (also known as spas). Although there are larger venues offering massage in the area, small-scale massage parlours are widespread and usually located above ground level. Signboards that protrude from buildings reveal their location, but they can be easily overlooked amongst the attention-grabbing shops and restaurants at street level.

A signboard reveals the location of a massage parlour on the street in Thamel.

Children were seen selling various types of food and goods on the street, including balloons, samosas and candy floss.

Business also takes place on the street itself. For example, the map shows (in blue): the street food stalls where vendors sell chatpati (dried noodles with spices); the cobbler who mends and cleans shoes on the street; and the cart where fresh spinach is sold. Amongst the vehicle traffic, goods were also being transported by cycle rickshaws.

The map shows where participants saw children working. Between 15 and 20 children were seen working in eight to ten businesses and on the street (in approximately 10% of businesses). This included nine children (five boys and four girls) who participants recorded as age 14 or under, and four children recorded as age 15 to 17 (three girls and one boy). Children were observed working in restaurants, in massage parlours, selling items on the street (samosas, balloons, chocolate, candy floss) and carrying tea from tea shops to various businesses.

The street

Participants observed the street in two shifts between 9am and 9pm on a Friday in April 2023. May is high season for tourism in Nepal. The activity in the street varied over the course of the day. One business owner noted:

‘In morning, the shutters were not open…around 75% of the businesses were closed.’

Female, business owner, research team

The street became busier by late afternoon, with a high flow of customers. Of those in the street, around 70% were male and 30% were female. Of these, approximately 20% were international and 80% domestic/regional tourists or locals.

As the character of the street changed in the evening, so did the street-based businesses. For example, one participant was surprised by street vendors’ adaptability:

‘…there was a street vendor; before sunset, he was working as a cobbler and after sun set, his stall changed to a panipuri (street food) stall’

Female, age 17, research team

In the evening, small nooks became places of enterprise: a street vendor set up a stand selling momo (steamed dumplings) by the ATM machines next to the dohori; street stalls began selling snacks; and touts started standing outside night venues to entice customers inside.

The type of customer and their behaviour also changed from early evening onwards. One child participant noted:

‘We saw some drunk people and we observed people using foul and abusive language’

Female, age 17, research team

Participants identified two places where there was more activity from early evening time onwards: one at the north end of the street close to a massage parlour and a small shed selling drinks and snacks, and the other at the south end of the street, close to a different massage parlour, khaja ghar and dance bar. In both places, participants noticed a higher concentration of young people (male and female), some of whom were under 18. They felt that these areas were less safe, particularly because people were drunk.

By late afternoon, the street is busy. The majority of people in the street are Nepalese men heading out for entertainment on a Friday evening, but there are also some international and regional tourists.

Sounds of the neighbourhood

Thamel music soundscape

As the character of the street changed in the evening, so did the street-based businesses. For example, one participant was surprised by street vendors’ adaptability:

…there was a street vendor; before sunset, he was working as a cobbler and after sun set, his stall changed to a panipuri (street food) stall.

Female, age 17, research team

In the evening, small nooks became places of enterprise: a street vendor set up a stand selling momo (steamed dumplings) by the ATM machines next to the dohori; street stalls began selling snacks; and touts started standing outside night venues to entice customers inside.

The type of customer and their behaviour also changed from early evening onwards. One child participant noted:

We saw some drunk people and we observed people using foul and abusive language.

Female, age 17, research team

Participants identified two places where there was more activity from early evening time onwards: one at the north end of the street close to a massage parlour and a small shed selling drinks and snacks, and the other at the south end of the street, close to a different massage parlour, khaja ghar and dance bar. In both places, participants noticed a higher concentration of young people (male and female), some of whom were under 18. They felt that these areas were less safe, particularly because people were drunk.

Where children were working

Working children were more prevalent in the afternoon and evening time. One business owner reflected:

In many places child labour was not seen in the morning, but in the evening, we could easily spot children working in many places. Maybe because of school – some children go to school in the morning and work in the evening.

Female, age 33, business owner, research team

Children were observed working in the massage parlour and khaja ghar in the area located at the southern end of the street. Their activities are described below (see ‘The building’ section).

In addition to this area at the southern end of the street, the research team observed children working in various other businesses and in the street itself. Children were observed in several restaurants on the street, either cooking, making juice, carrying 20 litre water jars, cleaning or serving customers. Some of the research team entered one of the restaurants and saw numerous children working there: one girl and several boys aged 14 and under. Children were seen selling snacks on the street plus goods such as balloons.

One boy was observed throughout the day, carrying tea to various businesses. He was first seen at around 9am when observations began and was still working when the researchers left the street at nearly 10pm. When one of the business owners asked him his age, he said that he was 13, but he looked as young as 10 years old. One business owner explained that he works in a tea shop and that she knew the owner.

We all observed a child selling tea. But when I enquired, I was told was that the child was not an employee, he was the brother of the owner. He said he studies in the sixth grade. I told him that I see him daily. He said he studies in the morning at school. When I asked [the child], do you get paid, he said no, the tea shop is owned by my own elder brother. But as per my observation, they are not siblings. I felt like that child was forced to tell made-up stories which had been told to him by the owner. Male, age 48, business owner, research team

His work is very risky as he gets abused by everyone. The traffic is dangerous here and all day long he is on the roads carrying tea and delivering in different areas Male, age 48, business owner, research team

On the day of the observation, a member of the research team observed the boy being slapped across the face by a shop employee.

….we saw a boy who entered a trekking store to bring back an empty glass [of tea that had been served earlier at the store]. When he left the store owner called him back rudely. Then he asked the child’s name and told him to return [in a humiliating way]’ Male, age 16, research team

We saw some child labour also which was surprising for me. I was the one who believed child labour was not that prevalent in the Thamel area, but I was proved wrong. Male, age 48, business owner, research team

A boy aged less than 14 years old was seen working for over 12 hours, carrying tea from a khaja ghar to various businesses in the street. He was seen being shouted at, belittled and hit over the course of the day.

By evening the street was busy. At times the electricity was cut, making the street darker and more intimidating.

The research team’s experience in the street

One stranger, around my age was harassing me. Female, age 16, research team

I was scared, to be honest. People stared at us, and it was uncomfortable for us. Female, age 16, research team

When the electricity went out, I got scared. I found out how people perceive girls when you stand on the street. Female, age 17, research team

The Building

At the southern end of the street, teenaged girls (aged between 13 and 16) were observed inside a massage parlour. The khaja ghar isa central point for dance bar and massage parlour workers to eat and hang out.

The research team selected a building that represented child labour in the street. A building at the southern end of the street was chosen which housed a number of medium scale businesses including a khaja ghar and/or small-scale eatery, a massage parlour and a dance bar.

The building is four storeys high. At ground level, there is a small khaja ghar selling momos (steamed dumplings). The eatery is simple: a table with a momo bada (steamer) atop a gas burner stands at the front of the shop with one or two tables and chairs behind it. The walls are painted bright green but there is little decoration. A dance bar is situated at the back of the building with the entrance along the side, further back from the main street. Several plastic chairs line the outside wall to the dance bar, and a few street stalls selling snacks from the early evening are set up on the opposite wall. Above the khaja ghar is a massage parlour. A sign board for a snooker/pool room could be seen on the floor above, but this business was not operating.

The research team chose the building highlighted in pink to represent child labour in the street. The building houses a khaja ghar, massage parlour and dance bar. Children were seen working in the massage parlour and the khaja ghar.

The children working in the building

The participants observed around 12 employees who were associated with the dance bar and/or massage parlour. They estimated that the majority were aged between 20 and 24 years of age. However, there were also a number of children observed in and around the building: an adolescent boy aged around 17 was seen working in the khaja ghar; the boy from the tea shop was seen talking with the street stall sellers and the young khaja ghar worker; and the two teenaged girls were seen in the massage parlour and later in the khaja ghar and the area surrounding the building.

some girls were there in the spa [massage parlour]. One was around 16 but she was not working [as a massage therapist]. She was wearing revealing clothes. Another one was even younger, and she was resting [lying down]. Male, age 48, business owner, research team

“In that spa (massage parlour) area, the vibes were not good. Female, age 17, research team

The research team noticed that the two teenage girls didn’t stay in the same place for an extended period of time but walked around the area. They chatted with the male staff of the dance bar who were sitting on the chairs outside (the child participants described the teenage girls as ‘teasing’ the men). When they were in the massage parlour, the girls were seen dancing, laughing and sitting with several other individuals who were mainly young women. Two men who seemed to be customers in their 40s or 50s (possibly regional tourists) entered the massage parlour together at around 8.30pm, followed by another man at 9pm. By 9.30pm the massage parlour had closed.

…when we went out monitoring visit the massage parlours and spas, there was no child labour, but yesterday there was child labour in a massage parlour Female, Age 33 Business owner, Research team

Participants noted that the building and its surrounding area was much more active after dark and that they felt this was a risky area.

The khaja ghar is a central meeting point for people working in a building that also houses a dance bar and a massage parlour.

Inter-relationships between businesses within the building

The research team reflected on how the businesses in the building interacted with one another. This included the way that business owners rented and sub-let parts of the building.

The massage parlour business takes up the whole building except for the ground floor which has the khaja ghar. The massage parlour owner pays rent on the whole building, (in this case NPR 130,000 / USD $980 per month) and rents out the ground floor to the khaja ghar Female, age 33, business owner, research team

The dance bar has a separate owner. Within this mini business eco-system, the khaja ghar is frequented by dance bar and massage parlour employees who use it as a space to hang out and eat. Two men in their 30s/40s were seen sitting for several hours, often talking to and hugging the women in their early 20s who seemed to be dance bar employees. The men were also seen visiting the massage parlour and counting money there. At one point the two young girls from the massage parlour entered the khaja ghar and were angrily shouted at by one of the men, before leaving the building. It is possible that the men were the owners or employees of the dance bar or one of the other businesses.

The khaja ghar appeared to be a convenient meeting point for individuals connected to the various businesses in the building. At ground level, it is well positioned to direct customers to the more discreet services available in the massage parlour above it. It is also a place for staff from the dance bar to eat cheaply and spend time when not working in the dance bar.

High rents

Rent for massage and spa is very expensive. Several unfortunate incidents have taken place in the venues of massage parlour and spa before so the rent is very expensive. Male, aged 48, business owner, research team

hotels are charged expensive (rates) but is bit less than the rent for massage parlours. Rent also depends on the floor of the building Female, age 37, business owner, research team

The massage parlour sector is predominantly run by women. Accompanying CLARISSA research with business owners has found that this is often because owners have progressed from working in massage parlours themselves to becoming owners in order to secure an income and look after their children as they get older.

Most of the spas are run by women and they are charged more by landlords. Female, age 33, business owner, research team

Given the high rental rates, the poor condition of the building that house massage parlours is notable.

The business owners in the research team noted the high rental rates in this area, which they felt were further inflated for massage parlours, due to the association of massage parlours with the sex industry and to several recent high-profile criminal cases related to trafficking (by a massage parlour owner) and the physical assault of a massage parlour employee.

Discussion

On a busy and vibrant street in Thamel, children were found working in various businesses, including those associated with the adult entertainment sector. The mixed nature of both the street and the clientele is notable: businesses such as massage parlours, khaja ghars and dance bars intermingle with high-end hotels and restaurants, (handicraft stores, fairtrade shops and banks. The proximity of these very different types of establishments speaks to Thamel’s unique history and location. From the 1970s, Thamel emerged as both a place for tourists to stay, shop and be entertained and a space where social norms related to sex, food and alcohol could be transgressed by the resident (predominantly male) population. As a result, the square mile Thamel occupies in the centre of Kathmandu is both densely populated and heterogenous; a ‘shared neighbourhood’ where sex-related services have become a relatively normalised part of the varied urban landscape (Giri Grant, M, 2014)[1]. Observations made over the course of a day also highlighted temporal changes to this landscape. While safeguarding concerns meant the research team could only observe the street until 9pm, the team noted changes to the nature of the street and type of customer by early evening when night entertainment venues were becoming more active.

The street, and in particular, venues related to adult entertainment, are set up to accommodate this varied and changing customer base. For example, soon after the massage parlours close, the dance bars begin to welcome customers, while a range of massage parlours provide different types of services depending on customers’ needs and desires. While some businesses provide only massage therapy, CLARISSA’s work accompanying a massage parlour business owner in Thamel documents an example of a massage parlour offering massage therapy alongside sexual services. But the research team’s observations in this Thamel street shows the sub-sector also includes establishments set up to facilitate only sexual services (e.g. they had no equipment or paraphernalia related to massage therapy) – the presence of which surprised even the massage parlour business owners who had been working in the sector for many years. This speaks to the discreet way in which businesses are run in the area, particularly given the history of a level of surveillance of massage parlour businesses, which makes it challenging even for ‘insiders’ to understand and navigate the complex landscape.

Within this mixed neighbourhood, while child labour was not intentionally hidden, the research team reflected on how the prevalence of child labour could be obscured because it was less overt and more dispersed compared to the street observed in Gongabu, for example. Child labour was described as being ‘hidden in plain sight’: working children were clearly visible on this central street in Thamel when the research team was looking for them but could easily go unnoticed due to the density of the buildings, intermingling of different types of business and varied clientele. Within this urban tapestry, even a very young boy being repeatedly abused could go unnoticed, as could two teenage girls in their mid-teens who the research team felt were involved in some form of child sexual exploitation.

Interlinkages between different types of adult entertainment business operating in close-proximity to each other were also seen on this street. The building the research team focused on, for example, could be described as a micro eco-system where a cluster of small to medium scale businesses interconnect to support each other: the larger, more formal dance bar business relying on more informal businesses such as the khaja ghar and snack shops, to feed employees and provide a space to hang out (and possibly a way to direct customers to the more discreetly located services within the same building); while the dance bar and massage parlour offer different services to those seeking sexual services from young women and girls.

The proximity of the businesses was reflected in the familiarity of the social interactions between different actors connected to these businesses such as the dance bar employees, customers and the teenage girls observed working in the massage parlour. But just as the entrepreneur working on the street transitioned from shoe-mending to selling street snacks after dark, CLARISSA’s research suggests that the proximity of different types of venue and connections between those working in them, provides opportunities for the fluid transition of workers (including children) between different businesses. This reflects the varied efforts both adults and children have to make when working in an urban centre. For some this may mean moving between businesses, in different roles, and navigating the varied risks each type of work entails.

[1] Grant, Melissa Gira. Playing the whore: The work of sex work. Verso Books, 2014.

The neighbourhood mapping process

CLARISSA neighbourhood mapping sought to understand children’s experience of urban neighbourhoods and to identify the characteristics of urban neighbourhoods that contribute to the emergence and perpetuation of Worst Forms of Child Labour. The research team was interested in mapping Thamel because it is an entertainment and tourist centre, that attracts both Kathmandu residents, and domestic and international tourists. Thamel has a high concentration of businesses that are associated with the adult entertainment sector including massage parlours, dance bars and dohoris, but also, many other businesses. Thamel is of particular interest because it has a range of types of business, both in terms of the services offered, the price-points they cater to, and their level of formality. We were interested to explore the relationships between these different businesses, and to explore where WFCL is found on a street with such a wide range of enterprise.

In Spring 2023, eight children (one boy and seven girls) aged 15 to 17 who had worked or were working in venues associated with the AES (dance bars, dohoris, khaja ghars, massage parlours or party palaces), and four business owners (three female and one male) who run massage parlours in Thamel or close by, undertook participatory neighbourhood mapping.

Following several scoping visits carried out by CLARISSA researchers and a massage parlour owner, 150m of a street in Thamel was selected to be mapped. The street was chosen because is one of the main streets in the area. The part of the street selected is representative of the diverse business landscape in the surrounding area.

CLARISSA researchers and practitioners from two local partner organisations (Platform for Children and Biswaas Nepal) accompanied the business owners and child participants on two field visits to map and observe the business landscape and the activities taking place in the street. During a first field visit, children and business owners worked in two groups to map each side of the street. To do this without drawing attention to themselves, they used mobile phones to take pictures and make audio recordings where they described the buildings. Following this visit, the two groups worked to create a base map in a workshop setting, reconstructing it using their detailed documentation from the field visit.

In a second field visit, children and business owners observed working children over the course of one day (between 9am and 9pm). They noted working children’s age, where they worked, the type of work or activity they were undertaking and the risks they were exposed to. Observations were mostly made from street level by making notes or audio recordings on mobile phones. Due to safeguarding concerns, children did not enter businesses to observe activities inside. Where they felt comfortable, business owners did enter businesses. This was usually where they had a good relationship with the employees or owner there.

In a second workshop, children and business owners worked together refine the base map and record their observations onto it with the support of researchers and the illustrator. A third, validation workshop, was then held to check the detail of the maps. It was also an opportunity for the children and business owners to reflect on their overall experiences and discuss the observations.