The centrality of children to a precarious business

The day-to-day realities of running an informal glove manufacturing business in Hazaribagh, Bangladesh

Introducing Janahara Begum and her business

Janahara Begum runs a small business manufacturing leather gloves in Hazaribagh, Dhaka in Bangladesh. She has worked in the leather sector for 22 years. When her first daughter was born, she was working in a garment factory. She went back to work when her daughter was four months old, leaving her with her sister during work hours. She used to go back home at lunch to feed her child. After struggling with this, a neighbour suggested she become a home-based worker making gloves. He helped her to get her first sub-contracts. This move allowed her to spend more time with her child.

Shortly afterwards she took a loan from a micro credit organisation, bought two sewing machines, and began her own business. Today, 21 years later, Janahara has two grown-up daughters. She rents a brick building with two rooms to run her enterprise. One room is mainly used for storing processed leather and other raw materials, and the other room is used for making gloves. The rooms are each around 10 square metres. The premises are extremely dark, with little natural or electric light. The factory is on the ground floor and the neighbouring building is than less than four metres away. There is no proper ventilation in the factory.

The business manufactures leather gloves used by construction workers, welders and ship breakers. Orders come from local buyers in Hazaribagh. Janahara does not have enough capital to buy ‘fresh’ leather, so she buys waste leather that has been rejected by other factories.

The business hires nine people. Seven of the workers are children. Five of the children are employed and two are irregular workers. They work 12 hours a day, six days a week. Adults and children are paid production-based wages, linked to the step in the process that they complete.

Outside the factory

Work shadowing with Janahara

A CLARISSA researcher accompanied Janahara for four consecutive days in December 2021. The purpose of the accompaniment or ‘work shadowing’ was to closely observe and gain an in-depth understanding of business processes, work practices, employer-employee relationships, business challenges and the mitigation strategies used by Janahara to operate the enterprise.

It was originally envisaged that two researchers would conduct the work shadowing exercise, but due to extremely limited space in the factory premises, only one researcher carried it out. The researcher stayed close to Janahara and her employees. They learned how to make gloves, asking questions and initiating informal discussions. They took detailed field notes. Over the four days, the researcher got to know the following staff:

Adults

- Janahara, the owner, in her 50s sews gloves and supervises the other workers.

- Mamun, who is in his 30’s, draws the outlines of gloves on leather before it is cut. Mamun is not a regular staff member; he is employed only when new orders come in. He is paid per piece of leather he cuts.

- Romela, in her 50’s, cuts leather and sometimes assists in drawing outlines. She only works when orders come in.

Children

- Aasia (14 years old) is Romela’s daughter. She assists her mother with cutting leather and is a temporary worker.

- Munia (17 years old) is also Romela’s daughter, assisting her mother when the business has an order.

- Borhan (17 years old) sews gloves.

- Ejaz (14 years old) ‘mills’ or ‘stamps’ leather to make it soft. This involves stamping up and down on the dry leather. Ejaz also dyes leather by stamping up and down on it in a barrel of chemicals.

- Rana (16 years old) also ‘mills’ or ‘stamps’ leather.

- Karim (12 years old) does various tasks such as trimming threads from the gloves. He is a new employee, and everyone calls him “Shishu” (child).

The shadowing experience was also an opportunity for the CLARISSA researcher to meet local buyers and observe business-to-business interactions.

What happened at the glove manufacturing business

Day 1

All the workers arrived at the factory by 8:45 am and started working independently. Mamum drew shapes of gloves on leather and Romela and her two daughters began cutting out the shapes with scissors. They also helped with the drawing. Borhan (17) and Janahara begin sewing gloves. Ejaz (14) and Rana (16) mill and stamp the leathers to make them soft. And Karim (12) starts trimming extra threads off the gloves.

The previous day (a Saturday) a large order had been due. The team had worked under pressure but had completed the order. At 9:30am Ejaz and Rana brought some paratha, dal and vegetables from a local restaurant. As there are no hand washing facilities in the factory premises, they ate without first washing their hands. This was their breakfast. The other workers had eaten at home before coming to work and did not take a break.

At 12:45 pm, a local buyer came into the factory to place an order for 100 pairs of gloves. There was a negotiation around price. The buyer suggested BDT 32 (US $0.29) for each pair of gloves. Janahara explained she could not produce the gloves for less than BDT 40 (US $0.36) given current prices of leather, chemicals and worker wages. BDT 36 (US $0.32) per pair was agreed, which was not felt to be a fair price by Janahara.

Before the buyer left Janahara asked for payment on a previous order, but the buyer said he did not have any money. She requested that he at least pay BDT 500 (US $4.50) since he was there, but he said goodbye and left.

At around 2pm everyone went home for lunch, returning one hour later, except for Romela and her daughters who did not return for the afternoon.

At 8:30 pm Janahara locked the door, and everyone left the factory for the day.

Day 2

Borhan came to the factory at 8:35 am and opened the door. Everyone arrived and started finishing the previous day’s work. Aasia and Karim started flipping and pushing the fingers of stitched gloves with iron sticks to bring them into shape.

At 11:30 am Ejaz and Rana brought out 100 pieces of leather from the storeroom to begin dyeing. For this process, the children used a plastic barrel (drum) with the upper portion of barrel cut down to be open. In one barrel they can dye 50 pieces of leather at a time. Ejaz and Rana filled the barrel with 50-52 litres of water, 800 grams of dye and 125 grams of chrome oil, which is known to cause a range of health issues including skin irritations, respiratory and kidney problems and cancers. The children put the leather into the barrel and then stamped on it for 15-30 minutes by standing in the drum with bare feet. Ejaz dyed 50 pieces of leather and then Rana did the same.

Later, Ejaz, Rana and Karim carried the dyed leather on their heads and shoulders up four storeys to the roof of the building to be dried under the sun. It was a hot, sunny day and by 2:30 pm the leather was dry. After lunch, Karim worked at cutting leather and sorting it. Janahara and Borhan sewed and Ejaz and Rana (16) were flipping and pushing the fingers of the stitched gloves with iron sticks.

At 9:00 pm the factory was closed, and everyone went home.

Day 3

On the third day of shadowing Janahara was not at the factory in the morning. The electricity went off at 9am. Borhan gave Ejaz BDT 10 ($0.10) to buy breakfast because Ejaz had not had breakfast at home. Karim also went to the shops to buy candles and food (paratha and vegetables).

The previous night there had been an announcement that there would be no electricity between 9-3pm due to maintenance. No sewing could be done due to the lack of electricity. The only work that could be undertaken was organising the leather by shape and flipping and pushing the fingers of the gloves. As such, the children spent time relaxing, gossiping and making fun of each other. Around 3pm, when the workers returned after lunch, the electricity came back on and regular work commenced.

Janahara came to the factory. Around 4pm a local buyer came to the factory to collect his order but was told that it was not ready due to the lack of power in the morning. He was asked to come back the next day. As Janahara had an instalment due on her loan with a micro credit organisation that day she asked the buyer to pay her BDT 2000 (US $18), but he declined, saying he had not brought money with him.

Later, as the factory had run out of leather, Ejaz and Rana went to a factory where Janahara’s husband was waiting with some waste leather. This was brought back to the factory by rickshaw van, where Ejaz, Rana, Borhan and Karim carried it on their heads to unload it into the storeroom.

At 8pm everyone went home.

Day 4

Janahara opened the factory at 9am. She sent Rana to a local shop to buy dye and chrome oil. At 11am she sent Karim to buy some snacks. The researcher accompanied Karim, noting how happy he seemed to be out of the factory. He spent some time talking with other children his age. He took a long time placing the order in the restaurant. He stopped to watch a football match some children were playing. After his return from the restaurant, Janahara scolded Karim for taking too long.

At 4:30 pm the buyer from the previous day returned to collect his order. He cleared some of the debt he owed Janahara.

Janahara runs the business out of necessity

Janahara came to Dhaka after she got married. Her husband did not have a good income and it was impossible to manage on his income alone. So, she began work in a garment factory. Once she had begun glove-making to juggle motherhood and work she progressed to being a small business owner quickly.

21 years later and Janahara is still working hard to keep her business going. Her husband delivers chemicals to factories and only earns between BDT 600-700 (US $5-6) a day, so she considers the business a necessity for their household income. She works the same hours as her workers and undertakes some of the core processes, for example sewing. She does not have enough capital to buy “fresh” leather and it is her husband who collects waste leather from different factories at a cheap price for her.

Despite these cost savings, Janahara feels that the living she makes from the business is precarious. She worries about how to service her debt and she accepts prices for orders that she feels are unfair.

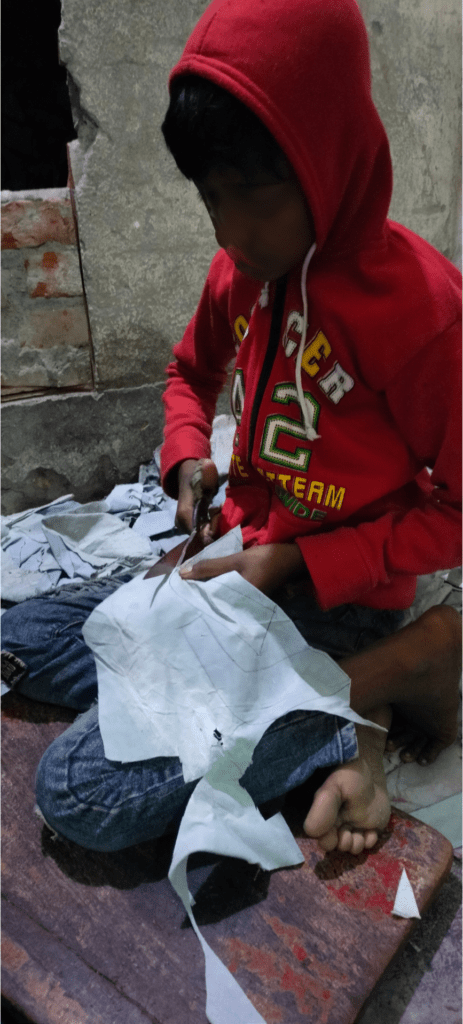

Factory interior and young worker

Buyers do not reliably pay

The cash flow in Janahara’s business is contingent on the good will of buyers. All business is negotiated verbally with individual buyers, and no written contracts are drawn up. Every sale requires a price negotiation and buyers often pay late.

Janahara was not happy about the price she agreed with the buyer, as she felt it did not represent the increasing price of leather, chemicals and employees, or the fact that the unit cost for gloves had also increased in the marketplace. She also expressed frustration that this buyer was not able to pay her in advance for the order, and indeed had not paid her for the last order they had placed with her. She explained:

“These people are not very good at payment. Always they make delays and want to give us less payment. But these products have huge demand in local construction, shipping and other sectors.”

Late payment causes stress and problems for Janahara, especially as she has loans that require regular payments, which she cannot make if she has not received payment for the gloves her factory has produced.

Janahara feels she has low bargaining power compared to the buyers and feels it might be possible to mitigate this by being part of some kind of small factory owners’ association. This would limit the extent to which buyers could take advantage of her.

Child working with chemicals

The business depends on child labour to operate

Most of the workers are children and they are integral to the running of the business. They are trusted to open the factory, handle money, run errands, mix toxic chemicals and work independently.

Direct and persistent exposure to chemicals like chrome oil without any safety measures is a particular concern, given what research says about the links between chromium and serious health problems, including skin diseases, respiratory problems and cancers.

The children working in this business find their relentless work schedule oppressive. During the shadowing, it was observed how they chose to play and joke around whenever they had an opportunity. It is notable however that the shadowing took place on quieter days. When organising the shadowing, Janahara advised us against starting on the Saturday because “we have huge work pressure. We have to deliver an order”. When Karim goes to the restaurant, he stops to watch the children playing football. He said:

“I love to play football, but I do not have any time to play. I go to the factory at 8:30 am and return home at 8 or 99pm During that time, no one plays.”

There was some evidence that Janahara’s work pressure is transferred to the children. While the researcher accompanied Rana on a trip to buy chrome oil she said:

“Our employer is not that bad. But sometimes, if we make mistakes she scolds us. Now, as you are here, she is not telling us anything.”

On Day four Janahara did express her frustration at the lack of productivity in front of a CLARISSA researcher when she had strong words with Karim, because he took a long time at the restaurant. This is an indication that the pressure Janahara feels is difficult to contain. At the same time, Janahara sees herself as a mother figure, through the work opportunities she provides. She recognises the position of need the children are in, as she herself is not much better off. She explained how she sees it:

“Workers are like my own children. I love them a lot. These poor kids come to my factory for work so that they can have some food. I hire them. I am running my business to meet my family expenses; if someone else can benefit from my factory, that’s also good.”

It was noticeable that children were given rice, vegetables and snacks at work. This seemed particularly important on the days children arrived without having eaten breakfast at home.

Conclusion

This small glove making business is precarious. It requires its owner and her workers to work 12 hours a day, six days a week to complete orders that are not adequately paid for by local buyers. It has also required her to take on loans from micro credit organisations, which she struggles to service.

70% of the workers in this business are children and it seems likely that this is a deliberate mitigation measure taken by the owner to reduce running costs and maintain operational viability. Profit margins are small. The business receives US $0.32 for each pair of gloves it makes and order sizes can be small. An order for 100 pairs of gloves will earn US $32, which needs to cover the rent, utility bills, leather, chemicals and production-based wages.

Their working environment is very poor. It is dark and dirty inside the factory and workers are exposed to dangerous chemicals and other hazards, including carrying heavy loads. The short-term solution to extreme poverty and deprivation that the business owner is offering children and families (by employing the children) may come at the expense of the children’s physical health in the medium to long-term.

Despite the hazardous nature of the work, the owner sees herself as a benefactor, acknowledging the poverty of the children who work for her. At least with work, they can eat. Although the children are eating, and not going hungry, none of the workers showed awareness about the dangerous nature of their work. It was more obvious that the children struggle with the long work hours, lamenting their lack of leisure time and enjoying whatever chance they get to relax and go outside the factory.

A child worker cutting leather